DrugWonks on Twitter

Tweets by @PeterPittsDrugWonks on Facebook

CMPI Videos

Video Montage of Third Annual Odyssey Awards Gala Featuring Governor Mitch Daniels, Montel Williams, Dr. Paul Offit and CMPI president Peter Pitts

Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels

Montel Williams, Emmy Award-Winning Talk Show Host

Paul Offit, M.D., Chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and the Director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, for Leadership in Transformational Medicine

CMPI president Peter J. Pitts

CMPI Web Video: "Science or Celebrity"

Tabloid Medicine

Check Out CMPI's Book

A Transatlantic Malaise

Edited By: Peter J. Pitts

Download the E-Book Version Here

CMPI Events

Donate

CMPI Reports

Blog Roll

AHRP

Better Health

BigGovHealth

Biotech Blog

BrandweekNRX

CA Medicine man

Cafe Pharma

Campaign for Modern Medicines

Carlat Psychiatry Blog

Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry: A Closer Look

Conservative's Forum

Club For Growth

CNEhealth.org

Diabetes Mine

Disruptive Women

Doctors For Patient Care

Dr. Gov

Drug Channels

DTC Perspectives

eDrugSearch

Envisioning 2.0

EyeOnFDA

FDA Law Blog

Fierce Pharma

fightingdiseases.org

Fresh Air Fund

Furious Seasons

Gooznews

Gel Health News

Hands Off My Health

Health Business Blog

Health Care BS

Health Care for All

Healthy Skepticism

Hooked: Ethics, Medicine, and Pharma

Hugh Hewitt

IgniteBlog

In the Pipeline

In Vivo

Instapundit

Internet Drug News

Jaz'd Healthcare

Jaz'd Pharmaceutical Industry

Jim Edwards' NRx

Kaus Files

KevinMD

Laffer Health Care Report

Little Green Footballs

Med Buzz

Media Research Center

Medrants

More than Medicine

National Review

Neuroethics & Law

Newsbusters

Nurses For Reform

Nurses For Reform Blog

Opinion Journal

Orange Book

PAL

Peter Rost

Pharm Aid

Pharma Blog Review

Pharma Blogsphere

Pharma Marketing Blog

Pharmablogger

Pharmacology Corner

Pharmagossip

Pharmamotion

Pharmalot

Pharmaceutical Business Review

Piper Report

Polipundit

Powerline

Prescription for a Cure

Public Plan Facts

Quackwatch

Real Clear Politics

Remedyhealthcare

Shark Report

Shearlings Got Plowed

StateHouseCall.org

Taking Back America

Terra Sigillata

The Cycle

The Catalyst

The Lonely Conservative

TortsProf

Town Hall

Washington Monthly

World of DTC Marketing

WSJ Health Blog

DrugWonks Blog

According to a report in Pharmtech.com:

“The Pharmaceutical Care Management Association (PCMA), an organization that represents the nation's leading pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which administer prescription drug plans for over 210 million Americans, released a new white paper investigating FDA’s influence on drug prices and competition in the pharmaceutical marketplace. The PCMA argues that competition within branded drugs is undervalued in FDA priorities and that FDA’s structures and regulations fundamentally hinder competition.”

The report's bias and ignorance can be summed up via this segment, “Without a statutory and regulatory agenda for the FDA that carefully examines the agency’s effect on pharmaceutical competition, some consumer welfare may be unnecessarily lost.”

Note to PCMA -- the FDA does not factor issues such as "competition" into it's regulatory calculations. Facts cannot be ignored because they are inconvenient.

The report takes specific aim at the FDA’s biosimilar pathway development process, stating that the delay in final guidance has “thwarted the development of a U.S. biosimilars industry—thus preventing the savings that competition would generate.” The report also calls out nomenclature issue for biosimilars as a potential impediment to the utilization of these products, and could also reduce the probability that drug makers would pursue a biosimilar for a product.

Wrong, wrong, and wrong.

Wrong that guidance should be rushed. (Isn’t it more important to get it right?) Wrong that discrete nomenclature will in any way deter use. (Isn’t it more important to ensure safety?) Wrong that manufacturers will decide to walk away because “it’s hard.” (Isn’t that table stakes?)

Speaking of transparency, it’s important to note that PBMs, such as Express Scripts, have a vested interest in keeping drug costs low. The PBM industry has largely supported the biosimilar movement from an early stage, as their utilization could produce an estimated 15% to 20% savings from innovator drug prices. This white paper screams, “cost over care.” According to Express Scripts President George Paz, “The cheapest drugs is (sic) where we make our profits.” (In 2008, Express Scripts agreed to pay $9.3 million to 28 states and $200,000 in reimbursement to consumers to settle lawsuits that accused the company of deceptive business practices in allegedly overstating the economic benefits to consumers of switching to certain drugs.)

Here’s the conclusion of the PharmaTech article:

“I believe the intent of Congress in providing a biosimilar pathway is to allow greater access through increased competition,” Peter Pitts, president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest and former FDA associate commissioner, told BioPharm International in a call. “The FDA’s job is to provide a pathway that’s transparent and predictable to allow enough companies to get into the game. If FDA doesn’t do that, it isn’t fully representing the intent of the legislation.”

Pitts believes FDA is doing the best job that it can, given the circumstances. “The creation of biosimilar regulations has to be a thoughtful and evolutionary process. The agency wants to make sure it’s as comprehensive as possible to create a level playing field.” Pitts adds, “The same proposition to transparency is relevant to nonbiologic, complex drugs as well, such as Lovenox.”

The complete PharmaTech article can be found here.

Read More & Comment...Much chatter about the Tuft’s Center’s new number for the cost of drug development.

Here’s the thoughtful comment from those lovely folks at Médecins Sans Frontières :

“The pharmaceutical industry-supported Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development claims it costs US$2.56 billion to develop a new drug today; but if you believe that, you probably also believe the earth is flat.”

NGO’s can poo-poo the important work of Joe DiMasi and crew this as much as they like – but serious analysis can’t just be tsk-tsked away by using the “industry-supported” evasion.

Here’s the news – and it’s important.

Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development Releases New Data on the Average Cost to Develop a New Medicine

The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development released new research on the average cost of drug development. The research conducted by Joseph DiMasi, Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, Henry Grabowski, Department of Economics, Duke University, and Ronald Hansen, William E. Simon School of Business, University of Rochester.

The estimates are based on research and development (R&D) costs for 106 randomly selected new drugs (87 small molecule drugs and 19 biologic medicines) obtained from a survey of 10 pharmaceutical firms The methodology used is consistent with prior research. The studies use compound-level data on the cost and timing of development for a random sample of new drugs first investigated in humans and annual company pharmaceutical R&D expenditures obtained through surveys of a number of pharmaceutical firms. The new compounds were first tested in humans anywhere in the world from 2005 and 2007 and development costs were obtained through 2013. [i]

The estimates represent the average cost of developing a new medicine, including the costs of the majority of compounds which do not make it through clinical trials, and the large cost of capital associated with the long-term investments required for drug discovery and development.

- The average R&D cost required to bring a new, FDA-approved medicine to patients is estimated to be $2.6 billion over the past decade (in 2013 dollars), including the cost of failures. When costs of post-approval R&D[ii] are included the cost estimate increases to $2.8 billion.

- Average R&D costs have more than doubled over the past decade.

*Previous research by same author estimated average R&D costs in the early 2000s at $1.2 billion in constant 2000 dollars (see J.A. DiMasi and H.G. Grabowski. "The Cost of Biopharmaceutical R&D: Is Biotech Different?" Managerial and Decision Economics 2007; 28: 469–479). That estimate was based on the same underlying survey as the author's estimates for the 1990s to early 2000s reported here ($800 million in constant 2000 dollars), but updated for changes in the cost of capital.

- The overall probability of clinical success (i.e., likelihood drug entering clinical testing will eventually be approved) was estimated to be 11.83%--this is significantly lower than the rate of 21.5% estimated previously.

- While the length of the process did not contribute to increases in R&D costs, it remained a very large share (45%) of total capitalized costs.

- Factors contributing to rising R&D costs cited by the researchers include:

o Increases in out-of-pocket costs for individual drugs are attributed to a range of factors including but not limited to increased clinical trial complexity and larger clinical trial sizes and a greater focus on targeting chronic and degenerative diseases.

o Higher failure rates for drugs tested in human subjects. The researchers noted an increase in the proportion of projects failing early, before reaching more costly Phase III trials.

These findings reinforce the challenges and complexities related to drug development, including technical challenges as companies are often focusing their R&D where the science is difficult and the failure risks are also higher.

For more information, please see: http://csdd.tufts.edu/news

[i] Note: the data are based on R&D projects there were self-originated. The study excludes R&D costs for licensed-in and co-developed compounds.

[ii] Post-approval R&D comprises efforts subsequent to original market approval to develop the active ingredient for new indications and patient populations, new dosage forms and strengths, and to conduct post-approval research required by regulatory authorities as a condition of original approval.

Pain patient advocate extraordinaire, Cindy Steinberg lays it on the line for Massachusetts Governor-Elect Charlie Baker.

Memo To Gov.-Elect: Include Pain Sufferers As You Seek Opiate Solution

By Cindy Steinberg

Cindy Steinberg is the policy chair for the Massachusetts Pain Initiative and the national director of policy and advocacy for the U.S. Pain Foundation.

“Charlie Baker vows to tackle state opiate problem,” was the Boston Globe headline two days after Election Day.

It’s good to hear from our newly elected governor that he plans to take steps to curb the ongoing problem with illegal use of prescription medication in our state. There’s little doubt that too many lives are being harmed by drug abuse and addiction.

But in a quest to fix one problem, policymakers need to consider the potential unintended negative consequences for the patients for whom these medications are a lifeline.

Gov.-elect Baker said in that Globe interview that he plans to convene a coalition of lawmakers, health care providers and labor leaders to confront the opioid crisis in our state. Representatives of the pain community — an estimated 1.2 million Massachusetts residents live with chronic pain — must be included in these discussions as well.

For many with chronic pain, the right medications mean the difference between a life worth living or not.

But despite these legitimate needs, more and more I’m hearing from residents of our state who are unable to access treatment that their doctors say they need and that they depend on. These are not addicts; these are people who are trying to manage their lives with debilitating conditions such as cancer, diabetic neuropathy, sickle cell, daily migraine, fibromyalgia, severe back pain and many others.

These are not addicts; these are people who are trying to manage their lives with debilitating conditions such as cancer, diabetic neuropathy, sickle cell, daily migraine, fibromyalgia.

Not including members of the pain community in discussions about how these medications are prescribed, regulated and controlled marginalizes the lives of thousands of Massachusetts citizens who live with pain caused by a myriad of conditions and serious injuries.

There is not a silver bullet solution to solving the abuse of prescription drugs. We need to take a thoughtful, multifaceted approach to ensure that those who need pain medication have access to it, and that those who choose to abuse these medications are stopped. There is no group more invested in making sure that medications are responsibly controlled than members of the pain community.

Last legislative session, Massachusetts lawmakers did take a step forward: they passed legislation on medications specially formulated to deter abuse.

“Abuse deterrent formulations” are opioids with physical and chemical properties that prevent chewing, crushing, grating, grinding, or extracting, or contain another substance that reduces or defeats the euphoria that those susceptible to substance abuse disorders experience. The new law requires insurance companies to provide the same coverage for the new abuse deterrent formulations as non-abuse deterrents, and they are not permitted to shift any additional cost of these medications to patients. It makes doctors more able to prescribe these medications without pushback from insurance companies.

Abuse deterrent formulations are not the only solution, but they are a good first step in balancing the legitimate needs of pain patients with the need to reduce medication abuse.

Other efforts must also include more robust education of medical professionals and of consumers to keep the medication out of the hands of potential abusers in the first place. Government statistics show that 78.5 percent of those who abuse prescription pain medication did not obtain them from a doctor themselves.

As someone who personally suffers from debilitating chronic pain, I have firsthand experience with the myriad challenges faced each day by the millions of Americans with severe chronic pain. I encourage Governor Baker to work to eliminate improper use of prescription medications, while remembering the medical needs of the chronic pain community.

Read More & Comment...

A new article in the DIA's Therapeutic Innovation and Regulatory Science journal discusses the pitfalls and potential for the FDA's openFDA program.

This past June, the FDA launched openFDA, a new initiative designed to make it easier for web developers, researchers, and the public to access large, important public health datasets collected by the agency.

The crowd-sourcing of adverse event data may or may not yield interesting results, but it’s a good place to start. It represents an opportunity for the agency to begin designing a more evolved approach to 21st-century pharmacovigilance.

To borrow a term from the nuclear disarmament discussion, 21st-century pharmacovigilance must work with its various colleagues to ‘‘trust, but verify.’’ Again, this fits hand-in-glove with the spirit of openFDA.

Access to data is important—but 21st-century pharmacovigilance must also take into consideration the realities of funding, existing staff levels and training programs, and existing regulatory authority. Perhaps creative public use of FDA data via openFDA will help develop not only new solutions but also awareness of the magnitude of the task at hand.

The full open FDA: An Open Question article can be found here.

A new agreement will expand access to Pfizer’s contraceptive, Sayana Press, for Women Most in Need in the World’s Poorest Countries. But there's more to story.

Per the Pfizer press release, “Collaboration will help advance progress and support global efforts to increase access to voluntary family planning information, services and contraceptives by 2020.”

Together with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, Pfizer has announced an agreement to expand access to it’s injectable contraceptive, Sayana Press (medroxyprogesterone acetate), for women most in need in 69 of the world’s poorest countries. Sayana Press will be sold for $1 per dose to qualified purchasers, who can help enable the poorest women in these countries to have access to the contraceptive at reduced or no cost.

John Young, President, Pfizer Global Established Pharma Business: “This is a great example of applying innovation to a Pfizer heritage product to help broaden access to family planning, Pfizer saw an opportunity to address the needs of women living in hard-to-reach areas, and specifically enhanced the product’s technology with public health in mind.””

The Pfizer/Gates/CIFF effort is a result of the July 2012 London Summit on Family Planning, which set an ambitious and achievable goal of providing an additional 120 million women in the world’s 69 poorest countries with access to voluntary family planning information and services by 2020.

John Young, “I’m so pleased with the leadership from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation and other collaborating organizations that are helping create a sustainable market through an approach that could be a model for other medicines.”

Bravo for Pfizer and partners. But the bigger story here is the creative redesign of legacy products for use in the developing world at low or no cost with NGO and other non-industry collaborators. It’s a model worth deeper investigation and broader implementation. Innovation comes in many forms.

Read More & Comment...

No one could explain Obamacare to stupid American votes... until a superhero from academia appeared.

Yes, Jonathan Gruber created a comic book character around his persona... I guess that's less narcissistic than naming the ACA Grubercare...

Read More & Comment...

Like Johnny Cash said, “I’ve been everywhere” -- or at least it seems that way. Over the past few months I’ve visited with government health officials in China, the Philippines, Malaysia, Egypt, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, Brazil, Columbia, South Africa, Kenya, and many other points in-between. And the only thing that’s grown more than my frequent flyer miles is my respect and admiration for those over-worked and under-appreciated civil servants toiling on the front lines of medicines regulation.

It’s a global fraternity of dedicated (and generally under-paid) healthcare and health policy professionals devoted to ensuring timely access to innovative medicines (Hong Kong), listening to the voice of the patient (the Philippines), pursuing post-market bioequivalence studies (Malaysia), developing biosimilar regulations (China), understanding the value of real world data (Colombia), guaranteeing the quality generics drugs (Egypt), promoting regulatory strategies for addressing non-communicable diseases.

But, just as in similar Western agencies (USFDA, EMA, Health Canada, etc.), “doing the right thing” is often a battle of evolving regulatory science, tight resources, competing priorities … and politics.

Many languages, priorities, pressures, and impediments (social, political, cultural), but one thing everyone agrees on is that quality counts. But what does “quality” mean – and does it mean the same thing from nation-to-nation and from product-to-product both innovator and generic? The good news is there’s general agreement that lower levels of quality for lower cost items aren’t acceptable. But the bad news is there are gaps and asymmetries in how “quality” is both defined (through the licensing process) and maintained (via pharmacovigilance practices).

Can there be a floor and a ceiling for global drug safety and quality? Even as we move toward differential pricing, should we allow some countries to have lower standards than others “based on local situations?” Can one man’s ceiling be another man’s floor? Can a substandard medicine ever be considered “safe and effective?”

Aristotle said, “Quality is not an act, it is a habit.” Habits are learned and improve with iterative learning and experience. And nowhere is that more evidently manifested than through the many and variable methodologies for generic medicines licensing and pharmacovigilance practices. From paper-only certification of bioequivalence testing and questionable API and excipient sourcing, the safety, effectiveness, and quality of some products are (to be generous) questionable.

Is this the fault of regulators; of unscrupulous purveyors of knowingly substandard products; of shortsighted, overly aggressive pricing and reimbursement authorities? While there are many different and important avenues of investigation, the most urgent area of investigation should focus on the asymmetries in how quality is defined, measured, and maintained. That which gets measured, gets done.

National 21st century pharmacovigilance practices must also take into consideration the realities of funding, existing staff levels, training programs, and existing regulatory authority. Accessing increased regulatory budgets is problematic. Should licensing agencies consider user-fees for post-market bioequivalence testing of critical dose drugs? That’s a contentious proposition– but agency funding is an often-overlooked 800-pound gorilla in the room and deserves to be seriously discussed and openly debated.

Another uneven issue is that of transparency. While regulatory standards are undeniably an issue of domestic sovereignty, shouldn’t there be transparency as to how any given nation defines quality? “Approved” means one thing in the context of the MHRA, the USFDA, and Health Canada (to choose only a few “gold standard” examples), but how can we measure the regulatory competencies of other national systems? Is that the responsibility of the historically opaque WHO? What about regional arbiters? Should there be “reference regulatory systems” as there are reference nations for pricing decisions? And how would this impact the concept of regulatory reciprocity?

And then there’s the danger of regulatory imperialism. Expecting other nations with less experience and resources to “harmonize” with the USFDA or the EMA isn’t the right approach. Rather we should seek regulatory convergence, because that gives us a pathway to improvement – with the first step being the identification of specific process asymmetries that can be addressed and corrected.

Two of the most important health advances of the past 200 years are public sanitation and a clean water supply. Those achievements helped to control as many public health scourges as medical interventions helped eradicate. In our globalized healthcare environment of SARS, Avian Flu, and Ebola, it’s important to remember that a rising tide floats all boats. It’s a small world after all.

Working together to raise the regulatory performance of all nations will help all nations to create sound foundations to address a multitude of regulatory dilemmas such the manufacturing of biosimilars, the control of API and excipient quality, pharmacovigilance and, yes, even counterfeiting.

Whether it’s in Cairo, or Amman, Riyadh, Brasilia, Kuala Lumpur, Dubai, Beijing, Bogota, Pretoria, Nairobi, or White Oak – a regulators work is never done. Global regulatory fraternity is essential to success. It’s about building capacity through collaboration.

Difficult? Surely. But, as Winston Churchill reminds us, “A pessimist sees the difficulty in every opportunity; an optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.”

Read More & Comment...Curiouser and curiouser.

From the Economic Times (of India):

Government panel moots clinical trial waiver for two cancer drugs

The (Indian) government's top advisory panel on medicines has recommended waiving off of clinical trials for two new cancer drugs, allowing them to be sold without testing on Indian patients. This, according to the panel, is permitted to cater to unmet medical needs.

The move is significant as it comes despite a recent directive from the Supreme Court asking the government to be careful while approving clinical trials as well as new medicines.

The two medicines - Aflibercept and Trastuzumab emtansine - are used in treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer and metastatic breast cancer respectively.

The Drug Technical Advisory Committee, headed by director general of health services Jagdish Prasad, considered that since both the drugs have been tested in various other countries and found to be effective, these can be allowed for sale in India in "public interest".

The law allows waiver of clinical trial in Indian population, only for drugs approved outside India, if there is national emergency, extreme urgency, epidemic, orphan drug or a disease for which there is no therapy.

However, many health experts feel the proposed clinical trial waiver to the two cancer drugs is in violation of rules and can have serious implications for patients.

According to CM Gulati, editor of the Monthly Index of Medical Specialities and an expert on the rational use of medicines, Aflibercept and Trastuzumab emtansine do not even qualify for exemption as there are alternative therapies available.

"This is a false and fabricated claim because there are other therapies available for metastatic breast cancer, notably Lapatinib plus Capecitabine. As a matter of fact Trastuzumab emtansine was compared with Lapatinib Plus Capecitabine for efficacy and safety," Gulati said.

Colorectal cancer, one of the lifestyle-related cancers, is still not much prevalent in India. Experts say the incidence of colorectral cancer in India is around 40,000 to 50,000 every year. Doctors say it is on rise as people are pursuing a western lifestyle and diet, high in protein and fat, low in fibre and vegetables.

On the other hand, breast cancer is developing into epidemic proportions in India with almost 1.5 lakh new cases being diagnosed every year and close to 70,000 women dying of breast cancer, according to Globocan (WHO) Data 2012.

As per the expert committee's suggestions, Aflibercept can provide for a second line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. However, experts contest that by this logic even third-line therapy and fourth-line therapy can be approved without conducting clinical trials on Indian patients.

However, there are also some who feel clinical trials can be waived for drugs that are available outside India for a specific period and which have therapeutic benefits.

"Generally clinical trials conducted in India do not come up with new data. On the contrary, trials cost a lot of money which consumers have to pay later. Moreover, it unnecessarily causes a delay in entry of crucial medicines," says Amit Sengupta, co-convenor of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, a public health advocacy movement.

Read More & Comment...Called it a system of draconian taxes

Called employer mandate a political fiction to raise taxes. But it is NOT central to law. Shouldn’t care where people get insurance.

Cadillac tax is really a 100 percent tax on cost of insurance (better than nothing)

Transparent spending is a fiction

Healthy people subsidize sick people except that percent of income ramps up over time..Points out that out of pocket costs will increase by 100 percent by 2018. It has already increased by 100 percent for chronically ill patients

150-200 pct of poverty will have deductibles of $3000.

Small business have limit on deductibles of $2000.

Limited networks: Not a good thing for patients. Gruber notes that people went to specialists less, hospital less. But not a long run solution.

Concluded by saying "We don’t have the right answer. Force politicians to be humble and patient.”

Well now you tell us. Better late than never.. Read More & Comment...

He ignores other aspects of the cost and value of medical innovation that take into account patient needs and long term impact.

True, spending on cancer treatments has climbed from $24 billion in 2004 to about $37 billion today. But that’s less than a half a percent of total US health-care spending.

More important: While expensive, since 2004 such innovations were largely responsible for a 40 percent increase in living cancer survivors, from 9.8 million to 13.6 million. The new therapies also saved $188 billion on hospitalizations.

In fact, a new study by Dr. Lee Newcomer confirms this result: United Healthcare’s cancer costs dropped as spending on new cancer drugs increased.

Finally, new drugs help people go back to work. The value of the increase in ability to work is 2.5 times what we spend on new therapies.

Presant's biggest problem, though, is that his cost diagnosis is one-size-fits-all: It treats all patients as the same, ignoring the genetic variation in patient response that a new class of “targeted” cancer drugs will soon address.

Dig a bit deeper, and it’s clear that Presant may have a more ideological motivation: By ignoring the role of insurers in jacking up the out of pocket cost of cancer drugs to discourage use, he sides with payors, not patients. It's the health plans that want docs to use 'pathways' -- back of the napkin calculations -- to make life and death decisions. Docs who stick to the pathways get bonuses and if they prescribe drugs outside the pathway they don't.

And this line of thinking does away with the Hippocratic Oath. No longer is the doctor’s first obligation “to apply for the benefit of the sick, all measures that are required.” Instead, Presant seems to believes three months of added life isn't worth it.

In fact, three months or less of survival can lead to a lifetime free from disease because average survival masks greater gains in many groups. Back in the 1980s, experts predicted AZT, the first anti-AIDS drug, would add less than three months of life. Yet nearly 90 percent of people taking AZT lived for two years. That allowed them to survive long enough to get the next-generation anti-retroviral combination that now keeps HIV in check.

Even when innovations don’t work miracles, refusing to die has a value not measured by the ASCO app.

When my friend Lynne Jacoby was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer in April 2012, she was told she’d die in weeks. She accepted the diagnosis, but not the prognosis. She entered a clinical trial and received an innovative treatment tailored to her tumors. She was able to travel, work and spend time with her wife and family.

Lynne died last Oct. 6, less than three weeks before her genome was to be sequenced for the next innovation. Her last written words measure the value of innovation Presant ignores:

“For someone like me, who is . . . told that my life would be measured in weeks, I guess I would just want everyone to realize that all of our lives are just measured in weeks, and we have to do whatever it takes to make that as many weeks as possible for everyone.” Read More & Comment...

According to Dr. Janet Woodcock (Director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research), opioid abuse-deterrence technology is in its “infancy” and FDA is unlikely to remove opioids that lack abuse-deterrence features from the market soon.

Speaking on the BioCentury This Week television program,Woodcock said approved abuse-deterrent opioids are “version 1.0.” FDA has approved three abuse-deterrent formulations, including Embeda morphine sulfate extended-release capsules with sequestered naltrexone from Pfizer; and reformulations of OxyContin oxycodone and Targiniq ER oxycodone/naloxone from Purdue Pharma. Woodcock added that there will be a “long path” to travel before FDA would require the incorporation of abuse-deterrence features as a condition for marketing opioids. Rather than forcing conventional opioids off the market, FDA is focused on getting more abuse-deterrent products approved, she said. “We are seeking input on how to get to a point where many, at least, of the formulations on the market have deterrent properties.”

Woodcock’s remarks come after the FDA’s public meeting on the future of abuse deterrent opioids. While the two-day session failed to produce any earth-shattering revelations, it did provide some additional insight into the agency’s strategic path forward. For example, the potential for swifter approval of generic AD products via truncated/bridge studies. One item that wasn’t on the agenda, but that was a topic of conversation during the breaks and after-hours was the increased pressure payers are putting on manufacturers to provide abuse-deterrent products.

That which gets measured gets done – and that which gets reimbursed gets manufactured.

Read More & Comment...Don’t Make Patients Pay for Insurers’ Mistakes

The health insurance industry continues to warn of financial ruin unless America institutes pharmaceutical price controls of the sort mainly found in Europe and Canada. Or, in the absence of regulatory action, insurers are simply sticking their customers with the tab through increased cost-sharing.

It would be highly unfortunate if the insurance industry campaign sparked bad policy decisions that hinder pharmaceutical innovators’ ability to respond to the next epidemic, such as Ebola. Or to illnesses such as hepatitis C that afflict some three million individuals and can lead to cirrhosis or liver cancer – and costs that can reach nearly $600,000 for a liver transplant.

Yet here we are debating miracle drugs that cost one-sixth of such pricey surgical procedures. Take Sovaldi, Gilead Sciences’ breakthrough hepatitis C drug, typically administered with ribavirin plus an interferon injection for a total cost of $94,726 for a full course of treatment (or around $150,000 if taken off-label with Johnson & Johnson’s Olysio, which eliminates the need for injections).

Gilead last week secured regulatory approval for an updated regimen, Harvoni, that combines the active ingredient in Sovaldi with protein inhibitor ledipasvir into a single pill with fewer side effects and a higher estimated cure rate. At $94,500, the price is slightly lower for a more effective, all-in-one oral treatment. Moreover, as many as 40 percent of hepatitis C patients can be cured with eight weeks of Harvoni treatment versus the typical 12-week course, at a significantly reduced $63,000 cost.

Insurers claim such prices will bust budgets and hurt patients (never mind that insurers are making patients pay more out of pocket), despite the fact that pre-Sovaldi hepatitis C treatments typically cost $65,000 to over $100,000. But these prior treatments were less effective and had greater side effects, so either had fewer takers or more patients prematurely ending their treatment. As the IMS Institute for Health Informatics noted in a recent report, “a key issue around the launch of [Sovaldi] is that payers did not accurately predict the demand from patients for the treatment or the price at which it would launch.”

The evidence suggests the industry had at least an inkling, however. Consider that pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts’s 2012 Drug Trend Report discussed the “increasing challenge of specialty prescription drug spending” and the fact that 22 new specialty drugs were approved in 2012, “many of which will cost more than $10,000 per month of treatment.” In August 2013, UnitedHealth Group’s pharmacy benefits management (PBM) unit published an article citing projected costs of as much as $100,000 for a full course of Sovaldi treatment.

What’s really happening is insurers want someone else to pay for their failure to adequately price demand for highly effective, potentially lifesaving drugs. If the critics had their way and new regulations required price slashing, inevitably patients would lose access to lifesaving therapies, both directly and as a result of reduced research and development expenditures on what could be the next Sovaldi, or Ebola-fighting ZMapp.

Insurers also are hardly powerless, which is evident in their ability to shift drug costs to patients. While critics lambaste the American health system as free enterprise run amok, in reality the U.S. health insurance sector is more like a regulated monopoly – with a mandated customer base that will keep growing as Obamacare expands its reach and as America continues to age. This gives insurers enormous power to bargain with providers and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Express Scripts, a vocal critic of specialty drug pricing, is a good example. As the largest PBM in the U.S. – with nearly $105 billion in 2013 revenue – Express Scripts enjoys enormous leverage in the marketplace. The company recently told its customers it planned to save $1 billion in 2015 by excluding 66 medicines from its list of covered drugs.

However, noticeably absent from the list was Sovaldi, for two reasons: one, they can’t afford not to cover a miracle drug with a 90 percent cure rate for a deadly disease that claims the lives of 15,000 Americans each year. And two, there is an explicit promise to drop Sovaldi once lower-priced competitors come online that demonstrate comparable effectiveness.

Meanwhile, insurers to date are hardly seeing major dents in their bottom lines. UnitedHealth, the first of the commercial payers to report earnings and an industry bellwether, released Q3 earnings that beat the Street’s expectations. At five percent, United’s overall medical cost increases were far below what they were a year ago at this time when they hit 13 percent, well before Sovaldi came to market. We’ll see what the other major commercial payers have to say, but thus far the concerns raised by the insurers’ Washington, D.C., lobbyists sounds like a case of tail-wags-dog.

Prescription drugs currently make up just over 11 percent of the nation’s nearly $3 trillion health care tab; simple math indicates pharmaceuticals are not the major driver of runaway U.S. health expenditures. America needs a national conversation on healthcare costs, not European-style price controls that will do nothing but deprive patients of potentially life-saving medicines. Insurers suffering through temporary blips in their stock prices should remember what’s really at stake, rather than waging expensive lobbying campaigns and engaging in scare tactics.

Peter J. Pitts, a former FDA Associate Commissioner, is President of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest. Read More & Comment...

Improved Access to Medical Innovation Slows Medicare Spending

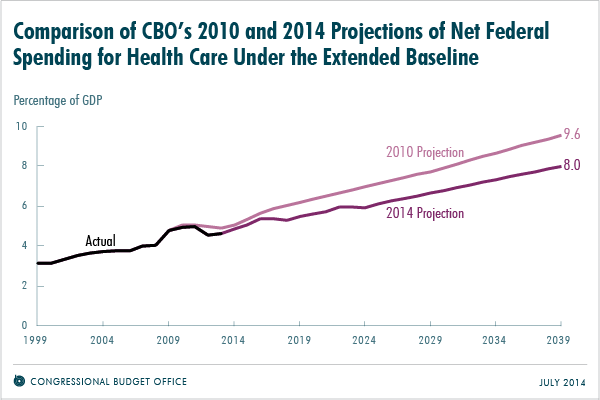

By: Peter J. PittsRecently the outlook for spending on federal health programs has been improving. While many have been quick to attribute the slowdown in the growth of spending to the Affordable Care Act, the data suggest improved access to prescription medications is the real hero.

The trustees of Social Security and Medicare recently reported that Medicare should have enough money in its trust through 2030, which is 13 years longer than they projected in 2009. Meanwhile the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected last month that federal spending on health programs in 2039 would equal 8.0 percent of gross domestic products (GDP), which is about 15 percent less than was projected in 2010.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

While some policymakers and journalists might conclude that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 is responsible, evidence of the decline actually predates the bill’s implementation. From 2000 to 2005, the annual growth in spending per Medicare beneficiary was 7.1 percent. But from 2007 to 2010, that rate dropped to 3.8 percent.

What changed between 2005 and 2007 was the introduction of Medicare Part D, which increased access and reduced the cost of prescription medications for millions of eligible Americans. As a result, prescriptions filled by Medicare beneficiaries jumped 14 percent in 2007.

In 2012, the CBO found that this increased use of medications was lowering Medicare’s spending on hospital and physician services. For every 1 percent increase in prescriptions filled by Medicare beneficiaries, spending on medical services dropped by about 0.2 percent, according to the agency.

The main driver of the decline in health care spending is increased access to prescription medications

A more recent analysis found that Medicare Part D reduced hospitalizations by 8 percent and saved the government about $1.5 billion during the program’s first four years. And Medicare Part D is costing less than expected, which is also contributing to the slowdown in health spending.

The main driver of the decline in health care spending is increased access to prescription medications. The health care system is using medication to control illnesses, and it’s replacing expensive hospitalizations, nursing homes and other medical services.

Medicare Part D provides prescription medication coverage for 35 million seniors through private insurers. Seniors pay low monthly premiums of $30 on average for their coverage and 90 percent said they felt satisfied with their prescription medication coverage in a recent survey. Not only is the program providing a valuable service, it is also costing 45 percent—or $348 billion—less than the original estimates — and with a more than 90 percent customer satisfaction.

The program works well because Part D medication prices are determined through negations between private insurers and manufacturers. The savings are realized because market competition effectively drives down the costs, and these savings are passed on to beneficiaries in the form of lower premiums.

Some government officials have proposed that the government should interfere with the program’s success by imposing new rebates on Part D medications. Such rebates, however, would reduce the savings from the program, increasing prices for Medicare Part D beneficiaries by up to 40 percent. The CBO has stated that government interference with the Part D negotiations between insurers and manufacturers would have a “negligible effect.” Precious few programs in Washington deliver both savings to the taxpayer and results to beneficiaries. On both counts, Medicare Part D succeeds. There isn’t a better model to recommend market-driven approaches to health care.

In contrast, the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) negotiates its own medication prices with manufacturers but excludes many newer therapies as a result. About 38 percent of drugs approved in the 1990s and 19 percent of the drugs approved since 2000 are not covered under the VA formulary, impacting the overall life expectancy of veterans. As a result, 40 percent of veterans with VA benefits choose to enroll in Medicare Part D instead.

While Medicare beneficiaries have affordable access to life-saving medicines, those enrolled in health insurance plans through the exchanges established by the ACA might not, thanks to specialty tier drug pricing.

Based on the CBO findings, it is abundantly clear, that medical innovation plays a critical role in the solution to curve health spending in the United States. Affordable access to life-saving therapies and continued support through pro-patient and pro-innovation policies are essential to improving patient lives, health care and the economy.

Read More & Comment...Washington Insider: Mistruths and half-truths about oncology meds

Demonizing new treatments distracts from the real problem: policies that focus on the near-term

There's been much legitimate consternation over the October 5th 60 Minutes segment on the cost of oncology meds. Hopefully the anger and indignation I've heard will drive some hard thinking toward smart and forceful actions to address the mistruths, half-truths, and straight-out lies presented during the program.

But why is anyone surprised? Did anyone expect a “fair and balanced” story from the same media that was complicit in helping to legitimize vaccine denial?

The 60 Minutes broadcast is only the most recent example of “value denial”—and it's important to understand the program not as a unique and unfortunate incident, but as a set-up for ASCO's pending announcement on it's new methodology for determining the cost-effectiveness of new cancer medicines.

But it's not cost effectiveness and it's not clinical effectiveness. It's a denial of personalized medicine. It is value denial.

Drugs aren't the cause of rising healthcare costs—they're the solution. Demonizing new treatments distracts from the real problem: top-down cost-centric policies that focus on the near-term, short-changing long-term patient outcomes, and so endangering “sustainable innovation” by denying fair reimbursement for high-risk investment in R&D.

New treatments are a bargain. Disease is always much more costly.

Until we counter the Orwellian newspeak that worships at the altar of the “high cost of drugs” with a fact-based and firm explanation of value, the minions of 60 Minutes will own the hearts and minds of the American public. And innovation loses.

And that is not acceptable.

Peter Pitts is a former FDA associate commissioner and president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest.

Read More & Comment...If you have any doubts that vaccines are on the cutting edge of innovation consider this, Pfizer has just received FDA-approval (via the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy Designation and Priority Review program) for Trumenda, a vaccine for the Prevention of Invasive Meningococcal B Disease in adolescents and young adults -- the first and only approved vaccine in the U.S. for the Prevention of Meningococcal Meningitis B.

As part of the accelerated approval process, Pfizer will complete its ongoing studies to confirm the effectiveness of Trumenda against diverse serogroup B strains.

The next time someone challenges the importance of innovation – trumpet Trumenda.

Read More & Comment...A consortium including European universities and medical groups plans to give experimental drugs to West African Ebola patients without assigning some to a placebo group, touching off an intense trans-Atlantic quarrel over what is ethical and effective in treating the virus.

Academics and medical groups in the U.K. and France, such as Oxford University, the Wellcome Trust, Doctors Without Borders and Institut Pasteur of France, have decided to give the drugs to sick African patients without randomly assigning other patients to a control group not getting the medicines. They say that in a ghastly epidemic, it is unethical to hold back treatment from anyone.

That has put them at odds with senior U.S. officials at the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Luciana L. Borio, FDA assistant commissioner for counterterrorism and emerging threats, told public-health officials at the World Health Organization in Geneva this month she was extremely concerned by the plans to give the medicines to patients without better evidence they work and aren’t highly toxic. “This is too urgent an issue for us not to start out with what we know is scientifically best,” said Dr. Borio. “The fastest and most definitive way to get answers about what are the best products is a randomized clinical trial.”

What crap. Randomized trials are not scientifically best, they are just tools no better -- probably worse -- than others to establish what works in who. Dr. Borio, spare us your holier than thou invocation of the randomize trial catechism...

Then there is this: The FDA yet again asked for more data on a drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a fatal disease that kills people before they are 30. The agency doesn't think the measure of response is statistically precise enough...

After receiving criticism the agency assured the public: "The FDA also plans to hold an expert advisory committee “to gain advice from outside experts and interested stakeholders on the adequacy of the data to support approval, including the possibility of ‘accelerated approval’—a mechanism to approve drugs in particular situations prior to the availability of definitive evidence of effectiveness.”

More crap.

The FDA had already received expert advice from Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, an advocacy group founded by family members frustrated by a lack of research on Duchenne muscular dystrophy, (who) initiated and wrote a draft guidance for pharmaceutical companies trying to develop drugs to treat the fatal condition.

... Read More & Comment...

Per reporting in BioCentury, in the first lawsuit filed by an originator company over a biosimilars application, Amgen alleged that Sandoz has unlawfully refused to follow the patent resolution protocol laid out by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA).

The suit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, concerns Sandoz's application to market a biosimilar version of Amgen's Neupogen filgrastim G-CSF, a recombinant methionyl human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Under BPCIA, Sandoz was required to provide Amgen with its BLA and manufacturing information for the biosimilar within 20 days of FDA’s decision to accept the application for review.

According to Amgen, Sandoz failed to disclose this information, thus depriving Amgen of the opportunity to assess potential patent infringement claims and potentially seek an injunction to prevent Sandoz from commercializing its biosimilar candidate. Amgen is seeking restitution for unfair competition and an injunction to prevent Sandoz from commercializing the biosimilar filgrastim until Amgen is "restored to the position it would have been [in] had Defendents met their obligations under the BPCIA."

Amgen is also seeking an injunction to prevent Sandoz from advancing through FDA's approval process until the company has obtained permission from Amgen to use the filgrastim license. Additionally, Amgen is seeking a judgment of patent infringement for U.S. patent No. 6,162,427. The suit also demands a jury trial.

Read More & Comment...The bill would add Ebola to FDA’s priority review voucher program, which Congress first authorized in 2007 to promote the development of new treatments and vaccines for neglected tropical diseases. Under the program, a developer of a treatment for a qualifying tropical disease receives a voucher for FDA priority review to be used with a second product of its choice, or this voucher can be sold.

It's an interesting idea worthy of immediate discussion and debate. Read More & Comment...

I don't think I have ever seen or read a more misleading, deceptive and outright false description of the drug development process. The gist of the article is that surrogate endpoints are not only useless, they are false markers of effectiveness that drug companies use to get worthless but profitable meds approved. Not suprisingly, a lot of so-called health care reporters have lauded MSJ piece as extraordinary journalism. Which just goes to show you that facts need not get in the way of a good story.

But for those who still care about facts, here they are:

Just this weekend at an educational forum about lymphoma, a well- respected hematologist-oncologist from a major medical center – not a drug company – supported the new FDA Breakthrough designation to approve drugs with significant data after phase 2 clinical trials. He says drugs approved on PH 2 data are now helping people with lymphoma. Conversely he notes that despite powerful PH 2 data for Gleevec, the FDA required an additional three years for Ph 3 data. He says, "A significant number of patients died during that period."

Let me put it this way: In short, the article is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the clinical trial process, confuses overall survival with the impact on life expectancy and concludes that what we need is to expose more people with incurable diseases to interminable waits that are a prolonged death sentence.

1. We are using surrogate endpoints to expedite Ebola treatments. We used them for HIV, Hepatitis C, heart disease, dozens of orphan drugs. The results: faster access, more lives saved. Would the authors oppose using surrogate endpoints — measures of disease progression used to estimate treatment response — for dying Ebola patients. Surrogate is not code word for fake or ineffective. Quite the contrary.

2. They imply that cancer trials take shortcuts. In fact, cancer drugs take longer to approve than many other types of medicines. And only 7 percent of cancer drugs get approved. If companies were controlling the drug development process you would think they would have better success!

3. The authors should have asked why haven’t we made even more progress? They blame surrogate endpoints when in fact they are looking relying upon randomized clinical trials that ignore subgroups of patients, surrogate endpoints that establish linkages between genotype and phenotype and genetic variations. They ignore the rapid growth in targeted therapies and the significant gains in quality of life and life expectancy they yield

4. As a result, The authors claim the solution is more randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and (we assume) the number of people enrolled in each trial. Setting aside the obvious result: an increase in the cost and time required to develop and use new products, this approach is based on wishful thinking and a willful ignorance of the genetic, molecular and clinical diversity that, when ignored, turn RCTs into an tool that harms patients.

Specifically, RCTs are totally inadequate in evaluating treatments in cancer therapy where genomic analysis is uncovering the tremendous heterogeneity of what was previously considered one disease, eg, colon cancer. Genomic analysis of individual patient’s cancers is disclosing the large number of mutations, and thus targets, within one person. Developing RCTs for targeted therapies would likely be impossible and heartless for those waiting for effective treatments.

For example, Bruce Chabner gives the example of PLX4032 for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. That compound had an 81 percent response rate in patients with BRAF mutations in a phase 1 trial. Yet in a phase III study, patients were randomized to PLX4032 or dacarbazine, which has a 15% response rate. Dr. Chabner and others ask whether it is ethical to randomize patients to a drug that everyone knows won’t work if you know in advance which treatment will work for whom.

"If patients with incurable disease who have the right biomarker for response are informed of these impressive early results they will want and perhaps deserve access to the new drug and may not accept random assignment to a modestly effective and toxic standard agent." (N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 24;364(12):1087-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1100548. Early accelerated approval for highly targeted cancer drugs.

Chabner BA)

Actual clinical RCTs are often statistically underpowered leading to inconclusive or incorrect results precisely because such studies are biased against prior knowledge. This is due in part to the effect of diminishing returns, because larger sample sizes are needed to achieve sufficient power capable of detecting the necessarily smaller positive effect sizes available as fitness improves.

5. Do potent cancer drugs carry risks? Of course. People also die surging surgery. We see the advertisements on TV - certain drugs for arthritis carry a risk of leukemia. But patients still want and need these potent drugs that change their quality of life! Drug approval is not always about survival, and it’s never risk free.

Read More & Comment...

That's a nice narrative but it is history rewritten by those who want to claim that every company in the drug or vaccine business should cut their prices or give away their products.

It is true that when Edward R. Murrow asked Jonas Salk who owned the patent to the polio vaccine Salk said: “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?"

Since then, Salk's statement has been use as trump card by individuals who claim that protecting the intellectual property of medicines is immoral or greedy. As an article in Slate notes: One critic of the big pharma called Salk “the foster parent of children around the world with no thought of the money he could make by withholding the vaccine from the children of the poor.”

Let's set aside the fact that solar energy companies have, in effect, patented the sun. There was a reason the Salk and the Sabin vaccines (more on that later) were not patented. The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis was the beneficiary of a massive campaign to eradicate polio that makes the ALS Foundation Ice Bucket Challenge and Standup2Cancer efforts seem anemic (which they are NOT.)

"In the single year that the polio vaccine was unveiled, 80 million people donated money to the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, which spearheaded the vaccine effort.... Schools, communities, and companies joined in a remarkable display of unity against the disease. Even Walt Disney’s cartoon characters contributed their talents, appearing in a film that adapted the Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ song “Heigh Ho” to an anti-polio ditty. In the 13 years leading up to the vaccine’s roll out, the budget of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis swelled from $3 million to $50 million.

In today's dollars that's about $500 million. The need for IP was removed because the passion capital had already been raised.

Further, it is true that a vaccine (an inactivated virus) does occur in nature as does the sun. But we patent both. How many solar energy companies have repurposed the sun's power with patented technology. A lot. And a lot more than vaccine companies have.

Then there is the myth that the Salk vaccine eliminated polio. In fact as Angela Matysiak noted in a review of a Salk biography:

"In 1959, epidemiologists reported findings on the pattern of the disease. These suggested a shift in incidence according to age, geography, and race. By 1960, less than one-third of the population under 40 years of age had received the full course of three doses of the Salk vaccine plus a booster. Most of those who had were white and from the middle and upper economic classes. The disease raged on in urban areas among African Americans and Puerto Ricans and in certain rural locales among Native Americans and members of isolated religious groups."

There were several reasons for the lag. Most important was the limited effectiveness of the Salk vaccine which was killed version of the polio virus required several shots. Matysiak oberves that Sabin put the point most succinctly: “The need for inoculating large amounts and the need for repetition are bad.” In contrast, an oral vaccine with a small dose of the attenuated versions of each of the three strains, administered once, would give lifelong immunity.

The Sabin vaccine was cheaper and easier to administer. But it became clear that both vaccines were needed because each protected certain subgroups that the other could not protect. The Salk vaccine could be used in people with compromised immune systems while the Sabin vaccine could not.

Both were required to eradicate polio. Ironically, the Sabin vaccine could be considered a me-too vaccine by the same ilk who claim patents don't matter.

And the same anti-patent crowd ignore another inconvenient truth: That Alexander Fleming, who discovered penicillin, regretted that he had not secure a patent because the lack of funding and private investment postponed it's development and commercialization by a decade and cost the lives of millions around the world.

Read More & Comment...

Social Networks

Please Follow the Drugwonks Blog on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube & RSS

Add This Blog to my Technorati Favorites