Latest Drugwonks' Blog

Called it a system of draconian taxes

Called employer mandate a political fiction to raise taxes. But it is NOT central to law. Shouldn’t care where people get insurance.

Cadillac tax is really a 100 percent tax on cost of insurance (better than nothing)

Transparent spending is a fiction

Healthy people subsidize sick people except that percent of income ramps up over time..Points out that out of pocket costs will increase by 100 percent by 2018. It has already increased by 100 percent for chronically ill patients

150-200 pct of poverty will have deductibles of $3000.

Small business have limit on deductibles of $2000.

Limited networks: Not a good thing for patients. Gruber notes that people went to specialists less, hospital less. But not a long run solution.

Concluded by saying "We don’t have the right answer. Force politicians to be humble and patient.”

Well now you tell us. Better late than never..

He ignores other aspects of the cost and value of medical innovation that take into account patient needs and long term impact.

True, spending on cancer treatments has climbed from $24 billion in 2004 to about $37 billion today. But that’s less than a half a percent of total US health-care spending.

More important: While expensive, since 2004 such innovations were largely responsible for a 40 percent increase in living cancer survivors, from 9.8 million to 13.6 million. The new therapies also saved $188 billion on hospitalizations.

In fact, a new study by Dr. Lee Newcomer confirms this result: United Healthcare’s cancer costs dropped as spending on new cancer drugs increased.

Finally, new drugs help people go back to work. The value of the increase in ability to work is 2.5 times what we spend on new therapies.

Presant's biggest problem, though, is that his cost diagnosis is one-size-fits-all: It treats all patients as the same, ignoring the genetic variation in patient response that a new class of “targeted” cancer drugs will soon address.

Dig a bit deeper, and it’s clear that Presant may have a more ideological motivation: By ignoring the role of insurers in jacking up the out of pocket cost of cancer drugs to discourage use, he sides with payors, not patients. It's the health plans that want docs to use 'pathways' -- back of the napkin calculations -- to make life and death decisions. Docs who stick to the pathways get bonuses and if they prescribe drugs outside the pathway they don't.

And this line of thinking does away with the Hippocratic Oath. No longer is the doctor’s first obligation “to apply for the benefit of the sick, all measures that are required.” Instead, Presant seems to believes three months of added life isn't worth it.

In fact, three months or less of survival can lead to a lifetime free from disease because average survival masks greater gains in many groups. Back in the 1980s, experts predicted AZT, the first anti-AIDS drug, would add less than three months of life. Yet nearly 90 percent of people taking AZT lived for two years. That allowed them to survive long enough to get the next-generation anti-retroviral combination that now keeps HIV in check.

Even when innovations don’t work miracles, refusing to die has a value not measured by the ASCO app.

When my friend Lynne Jacoby was diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer in April 2012, she was told she’d die in weeks. She accepted the diagnosis, but not the prognosis. She entered a clinical trial and received an innovative treatment tailored to her tumors. She was able to travel, work and spend time with her wife and family.

Lynne died last Oct. 6, less than three weeks before her genome was to be sequenced for the next innovation. Her last written words measure the value of innovation Presant ignores:

“For someone like me, who is . . . told that my life would be measured in weeks, I guess I would just want everyone to realize that all of our lives are just measured in weeks, and we have to do whatever it takes to make that as many weeks as possible for everyone.”

According to Dr. Janet Woodcock (Director of FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research), opioid abuse-deterrence technology is in its “infancy” and FDA is unlikely to remove opioids that lack abuse-deterrence features from the market soon.

Speaking on the BioCentury This Week television program,Woodcock said approved abuse-deterrent opioids are “version 1.0.” FDA has approved three abuse-deterrent formulations, including Embeda morphine sulfate extended-release capsules with sequestered naltrexone from Pfizer; and reformulations of OxyContin oxycodone and Targiniq ER oxycodone/naloxone from Purdue Pharma. Woodcock added that there will be a “long path” to travel before FDA would require the incorporation of abuse-deterrence features as a condition for marketing opioids. Rather than forcing conventional opioids off the market, FDA is focused on getting more abuse-deterrent products approved, she said. “We are seeking input on how to get to a point where many, at least, of the formulations on the market have deterrent properties.”

Woodcock’s remarks come after the FDA’s public meeting on the future of abuse deterrent opioids. While the two-day session failed to produce any earth-shattering revelations, it did provide some additional insight into the agency’s strategic path forward. For example, the potential for swifter approval of generic AD products via truncated/bridge studies. One item that wasn’t on the agenda, but that was a topic of conversation during the breaks and after-hours was the increased pressure payers are putting on manufacturers to provide abuse-deterrent products.

That which gets measured gets done – and that which gets reimbursed gets manufactured.

Don’t Make Patients Pay for Insurers’ Mistakes

The health insurance industry continues to warn of financial ruin unless America institutes pharmaceutical price controls of the sort mainly found in Europe and Canada. Or, in the absence of regulatory action, insurers are simply sticking their customers with the tab through increased cost-sharing.

It would be highly unfortunate if the insurance industry campaign sparked bad policy decisions that hinder pharmaceutical innovators’ ability to respond to the next epidemic, such as Ebola. Or to illnesses such as hepatitis C that afflict some three million individuals and can lead to cirrhosis or liver cancer – and costs that can reach nearly $600,000 for a liver transplant.

Yet here we are debating miracle drugs that cost one-sixth of such pricey surgical procedures. Take Sovaldi, Gilead Sciences’ breakthrough hepatitis C drug, typically administered with ribavirin plus an interferon injection for a total cost of $94,726 for a full course of treatment (or around $150,000 if taken off-label with Johnson & Johnson’s Olysio, which eliminates the need for injections).

Gilead last week secured regulatory approval for an updated regimen, Harvoni, that combines the active ingredient in Sovaldi with protein inhibitor ledipasvir into a single pill with fewer side effects and a higher estimated cure rate. At $94,500, the price is slightly lower for a more effective, all-in-one oral treatment. Moreover, as many as 40 percent of hepatitis C patients can be cured with eight weeks of Harvoni treatment versus the typical 12-week course, at a significantly reduced $63,000 cost.

Insurers claim such prices will bust budgets and hurt patients (never mind that insurers are making patients pay more out of pocket), despite the fact that pre-Sovaldi hepatitis C treatments typically cost $65,000 to over $100,000. But these prior treatments were less effective and had greater side effects, so either had fewer takers or more patients prematurely ending their treatment. As the IMS Institute for Health Informatics noted in a recent report, “a key issue around the launch of [Sovaldi] is that payers did not accurately predict the demand from patients for the treatment or the price at which it would launch.”

The evidence suggests the industry had at least an inkling, however. Consider that pharmacy benefits manager Express Scripts’s 2012 Drug Trend Report discussed the “increasing challenge of specialty prescription drug spending” and the fact that 22 new specialty drugs were approved in 2012, “many of which will cost more than $10,000 per month of treatment.” In August 2013, UnitedHealth Group’s pharmacy benefits management (PBM) unit published an article citing projected costs of as much as $100,000 for a full course of Sovaldi treatment.

What’s really happening is insurers want someone else to pay for their failure to adequately price demand for highly effective, potentially lifesaving drugs. If the critics had their way and new regulations required price slashing, inevitably patients would lose access to lifesaving therapies, both directly and as a result of reduced research and development expenditures on what could be the next Sovaldi, or Ebola-fighting ZMapp.

Insurers also are hardly powerless, which is evident in their ability to shift drug costs to patients. While critics lambaste the American health system as free enterprise run amok, in reality the U.S. health insurance sector is more like a regulated monopoly – with a mandated customer base that will keep growing as Obamacare expands its reach and as America continues to age. This gives insurers enormous power to bargain with providers and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Express Scripts, a vocal critic of specialty drug pricing, is a good example. As the largest PBM in the U.S. – with nearly $105 billion in 2013 revenue – Express Scripts enjoys enormous leverage in the marketplace. The company recently told its customers it planned to save $1 billion in 2015 by excluding 66 medicines from its list of covered drugs.

However, noticeably absent from the list was Sovaldi, for two reasons: one, they can’t afford not to cover a miracle drug with a 90 percent cure rate for a deadly disease that claims the lives of 15,000 Americans each year. And two, there is an explicit promise to drop Sovaldi once lower-priced competitors come online that demonstrate comparable effectiveness.

Meanwhile, insurers to date are hardly seeing major dents in their bottom lines. UnitedHealth, the first of the commercial payers to report earnings and an industry bellwether, released Q3 earnings that beat the Street’s expectations. At five percent, United’s overall medical cost increases were far below what they were a year ago at this time when they hit 13 percent, well before Sovaldi came to market. We’ll see what the other major commercial payers have to say, but thus far the concerns raised by the insurers’ Washington, D.C., lobbyists sounds like a case of tail-wags-dog.

Prescription drugs currently make up just over 11 percent of the nation’s nearly $3 trillion health care tab; simple math indicates pharmaceuticals are not the major driver of runaway U.S. health expenditures. America needs a national conversation on healthcare costs, not European-style price controls that will do nothing but deprive patients of potentially life-saving medicines. Insurers suffering through temporary blips in their stock prices should remember what’s really at stake, rather than waging expensive lobbying campaigns and engaging in scare tactics.

Peter J. Pitts, a former FDA Associate Commissioner, is President of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest.

Improved Access to Medical Innovation Slows Medicare Spending

By: Peter J. PittsRecently the outlook for spending on federal health programs has been improving. While many have been quick to attribute the slowdown in the growth of spending to the Affordable Care Act, the data suggest improved access to prescription medications is the real hero.

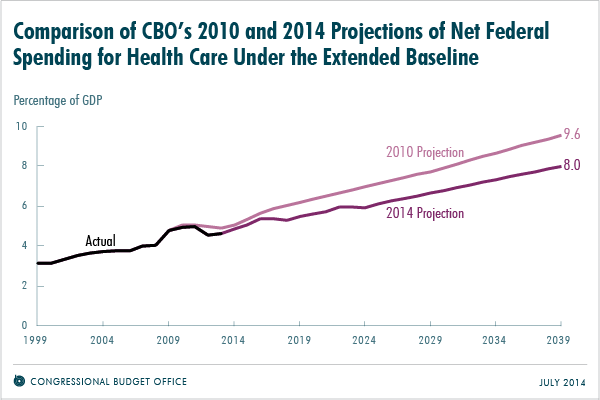

The trustees of Social Security and Medicare recently reported that Medicare should have enough money in its trust through 2030, which is 13 years longer than they projected in 2009. Meanwhile the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected last month that federal spending on health programs in 2039 would equal 8.0 percent of gross domestic products (GDP), which is about 15 percent less than was projected in 2010.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

While some policymakers and journalists might conclude that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 is responsible, evidence of the decline actually predates the bill’s implementation. From 2000 to 2005, the annual growth in spending per Medicare beneficiary was 7.1 percent. But from 2007 to 2010, that rate dropped to 3.8 percent.

What changed between 2005 and 2007 was the introduction of Medicare Part D, which increased access and reduced the cost of prescription medications for millions of eligible Americans. As a result, prescriptions filled by Medicare beneficiaries jumped 14 percent in 2007.

In 2012, the CBO found that this increased use of medications was lowering Medicare’s spending on hospital and physician services. For every 1 percent increase in prescriptions filled by Medicare beneficiaries, spending on medical services dropped by about 0.2 percent, according to the agency.

The main driver of the decline in health care spending is increased access to prescription medications

A more recent analysis found that Medicare Part D reduced hospitalizations by 8 percent and saved the government about $1.5 billion during the program’s first four years. And Medicare Part D is costing less than expected, which is also contributing to the slowdown in health spending.

The main driver of the decline in health care spending is increased access to prescription medications. The health care system is using medication to control illnesses, and it’s replacing expensive hospitalizations, nursing homes and other medical services.

Medicare Part D provides prescription medication coverage for 35 million seniors through private insurers. Seniors pay low monthly premiums of $30 on average for their coverage and 90 percent said they felt satisfied with their prescription medication coverage in a recent survey. Not only is the program providing a valuable service, it is also costing 45 percent—or $348 billion—less than the original estimates — and with a more than 90 percent customer satisfaction.

The program works well because Part D medication prices are determined through negations between private insurers and manufacturers. The savings are realized because market competition effectively drives down the costs, and these savings are passed on to beneficiaries in the form of lower premiums.

Some government officials have proposed that the government should interfere with the program’s success by imposing new rebates on Part D medications. Such rebates, however, would reduce the savings from the program, increasing prices for Medicare Part D beneficiaries by up to 40 percent. The CBO has stated that government interference with the Part D negotiations between insurers and manufacturers would have a “negligible effect.” Precious few programs in Washington deliver both savings to the taxpayer and results to beneficiaries. On both counts, Medicare Part D succeeds. There isn’t a better model to recommend market-driven approaches to health care.

In contrast, the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) negotiates its own medication prices with manufacturers but excludes many newer therapies as a result. About 38 percent of drugs approved in the 1990s and 19 percent of the drugs approved since 2000 are not covered under the VA formulary, impacting the overall life expectancy of veterans. As a result, 40 percent of veterans with VA benefits choose to enroll in Medicare Part D instead.

While Medicare beneficiaries have affordable access to life-saving medicines, those enrolled in health insurance plans through the exchanges established by the ACA might not, thanks to specialty tier drug pricing.

Based on the CBO findings, it is abundantly clear, that medical innovation plays a critical role in the solution to curve health spending in the United States. Affordable access to life-saving therapies and continued support through pro-patient and pro-innovation policies are essential to improving patient lives, health care and the economy.

Washington Insider: Mistruths and half-truths about oncology meds

Demonizing new treatments distracts from the real problem: policies that focus on the near-term

There's been much legitimate consternation over the October 5th 60 Minutes segment on the cost of oncology meds. Hopefully the anger and indignation I've heard will drive some hard thinking toward smart and forceful actions to address the mistruths, half-truths, and straight-out lies presented during the program.

But why is anyone surprised? Did anyone expect a “fair and balanced” story from the same media that was complicit in helping to legitimize vaccine denial?

The 60 Minutes broadcast is only the most recent example of “value denial”—and it's important to understand the program not as a unique and unfortunate incident, but as a set-up for ASCO's pending announcement on it's new methodology for determining the cost-effectiveness of new cancer medicines.

But it's not cost effectiveness and it's not clinical effectiveness. It's a denial of personalized medicine. It is value denial.

Drugs aren't the cause of rising healthcare costs—they're the solution. Demonizing new treatments distracts from the real problem: top-down cost-centric policies that focus on the near-term, short-changing long-term patient outcomes, and so endangering “sustainable innovation” by denying fair reimbursement for high-risk investment in R&D.

New treatments are a bargain. Disease is always much more costly.

Until we counter the Orwellian newspeak that worships at the altar of the “high cost of drugs” with a fact-based and firm explanation of value, the minions of 60 Minutes will own the hearts and minds of the American public. And innovation loses.

And that is not acceptable.

Peter Pitts is a former FDA associate commissioner and president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest.

If you have any doubts that vaccines are on the cutting edge of innovation consider this, Pfizer has just received FDA-approval (via the agency’s Breakthrough Therapy Designation and Priority Review program) for Trumenda, a vaccine for the Prevention of Invasive Meningococcal B Disease in adolescents and young adults -- the first and only approved vaccine in the U.S. for the Prevention of Meningococcal Meningitis B.

As part of the accelerated approval process, Pfizer will complete its ongoing studies to confirm the effectiveness of Trumenda against diverse serogroup B strains.

The next time someone challenges the importance of innovation – trumpet Trumenda.

A consortium including European universities and medical groups plans to give experimental drugs to West African Ebola patients without assigning some to a placebo group, touching off an intense trans-Atlantic quarrel over what is ethical and effective in treating the virus.

Academics and medical groups in the U.K. and France, such as Oxford University, the Wellcome Trust, Doctors Without Borders and Institut Pasteur of France, have decided to give the drugs to sick African patients without randomly assigning other patients to a control group not getting the medicines. They say that in a ghastly epidemic, it is unethical to hold back treatment from anyone.

That has put them at odds with senior U.S. officials at the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Luciana L. Borio, FDA assistant commissioner for counterterrorism and emerging threats, told public-health officials at the World Health Organization in Geneva this month she was extremely concerned by the plans to give the medicines to patients without better evidence they work and aren’t highly toxic. “This is too urgent an issue for us not to start out with what we know is scientifically best,” said Dr. Borio. “The fastest and most definitive way to get answers about what are the best products is a randomized clinical trial.”

What crap. Randomized trials are not scientifically best, they are just tools no better -- probably worse -- than others to establish what works in who. Dr. Borio, spare us your holier than thou invocation of the randomize trial catechism...

Then there is this: The FDA yet again asked for more data on a drug for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a fatal disease that kills people before they are 30. The agency doesn't think the measure of response is statistically precise enough...

After receiving criticism the agency assured the public: "The FDA also plans to hold an expert advisory committee “to gain advice from outside experts and interested stakeholders on the adequacy of the data to support approval, including the possibility of ‘accelerated approval’—a mechanism to approve drugs in particular situations prior to the availability of definitive evidence of effectiveness.”

More crap.

The FDA had already received expert advice from Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, an advocacy group founded by family members frustrated by a lack of research on Duchenne muscular dystrophy, (who) initiated and wrote a draft guidance for pharmaceutical companies trying to develop drugs to treat the fatal condition.

...

Per reporting in BioCentury, in the first lawsuit filed by an originator company over a biosimilars application, Amgen alleged that Sandoz has unlawfully refused to follow the patent resolution protocol laid out by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCIA).

The suit, filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, concerns Sandoz's application to market a biosimilar version of Amgen's Neupogen filgrastim G-CSF, a recombinant methionyl human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Under BPCIA, Sandoz was required to provide Amgen with its BLA and manufacturing information for the biosimilar within 20 days of FDA’s decision to accept the application for review.

According to Amgen, Sandoz failed to disclose this information, thus depriving Amgen of the opportunity to assess potential patent infringement claims and potentially seek an injunction to prevent Sandoz from commercializing its biosimilar candidate. Amgen is seeking restitution for unfair competition and an injunction to prevent Sandoz from commercializing the biosimilar filgrastim until Amgen is "restored to the position it would have been [in] had Defendents met their obligations under the BPCIA."

Amgen is also seeking an injunction to prevent Sandoz from advancing through FDA's approval process until the company has obtained permission from Amgen to use the filgrastim license. Additionally, Amgen is seeking a judgment of patent infringement for U.S. patent No. 6,162,427. The suit also demands a jury trial.

The bill would add Ebola to FDA’s priority review voucher program, which Congress first authorized in 2007 to promote the development of new treatments and vaccines for neglected tropical diseases. Under the program, a developer of a treatment for a qualifying tropical disease receives a voucher for FDA priority review to be used with a second product of its choice, or this voucher can be sold.

It's an interesting idea worthy of immediate discussion and debate.